Junior School intern teachers are increasingly speaking out about the harsh realities of their work—low pay, heavy responsibilities and continuous policy uncertainty. Their take-home salary, less than Sh18,000 after deductions, is far below what experienced teachers earn, yet interns are required to perform the same duties.

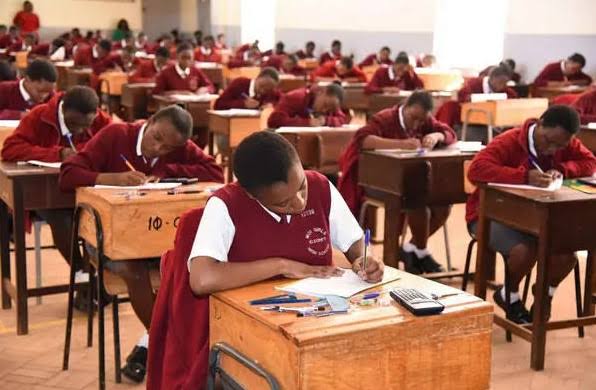

From lesson planning to assessments, classroom management to extracurricular activities, interns shoulder full teaching responsibilities. Many say they feel exploited and undervalued.

Teacher associations argue that the government has institutionalised cheap labour by creating a model that benefits from highly trained professionals while paying them a fraction of a full salary. KEJUSTA has even described the programme as illegal, citing a previous Labour Court ruling that flagged the internship structure for violating employment standards.

Intern teachers say the psychological toll is significant. Many entered the programme believing they would be quickly absorbed into permanent jobs. Instead, shifting government statements—from one-year timelines to two-year mandates—have deepened their frustration.

The workload itself is overwhelming. With Junior School facing a shortage of 72,000 teachers, interns are spread thin, often covering multiple subjects and classes.

Many say they love teaching but feel the system is taking advantage of their passion. Others report that financial strain has pushed them into debt, side jobs and burnout.

Education experts warn that demoralised teachers directly impact learning quality. If interns feel devalued, unsupported and trapped in temporary contracts, the outcomes of CBE will suffer.

As pressure mounts, stakeholders demand a fairer system—better pay, clearer timelines and humane conditions. Interns insist that teaching cannot thrive under exploitation, and call on the government to reform the internship programme before the profession loses more talent.