The push for junior school autonomy is gaining momentum, with unions warning of possible legal action if their demands are ignored. Leaders of the Kenya Union of Post Primary Education Teachers (KUPPET) argue that the current arrangement violates the structure of the competency-based curriculum and undermines effective learning.

According to KUPPET officials, housing junior schools within primary institutions has created conflicts, harassment, and mismanagement. Head teachers, who control both sections, are accused of sidelining junior school needs and diverting resources.

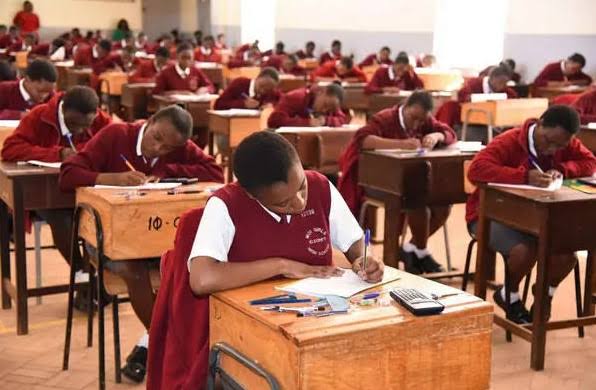

In Bungoma, KEJUSTA official Ladyisar Simiyu reported that many learners lack basic facilities such as desks, while co-curricular programs are neglected. Teachers also say that laboratory and library facilities remain unequipped, stalling crucial aspects of CBC delivery.

In Kwale County, allegations of harassment have worsened tensions. Teachers say they are often forced into non-teaching duties, such as cooking, while also managing high teaching loads. KUPPET executive secretary Leonard Oronje highlighted cases of teachers handling up to 40 lessons a week, which he termed “humanly impossible.”

Union leaders argue that autonomy would solve these challenges. By separating junior schools, funds could be directly allocated to their needs, administration streamlined, and teachers given a chance to work in dignity.

They also reject the Teachers Service Commission’s proposal to create comprehensive schools with principals and deputies overseeing both sections. According to KEJUSTA chairperson James Odhiambo, such a structure would fuel more disputes and dilute accountability.

Instead, teachers want recognition of junior schools as standalone institutions, aligned with the CBC’s 2-6-3-3 structure. “If the Ministry fails to respond, we will move to court to enforce what we believe is the rightful structure,” said Mr Oronje.

Beyond autonomy, unions are demanding confirmation of teachers currently serving as interns and the recruitment of more staff to reduce workloads. They also call for reforms in examinations, opposing the proliferation of commercial tests that burden both parents and teachers.

With demonstrations already erupting in Nyeri and murmurs growing nationwide, the government faces mounting pressure. For unions, the legal route may be the next step, signaling a potential showdown that could reshape the future of junior school education in Kenya.